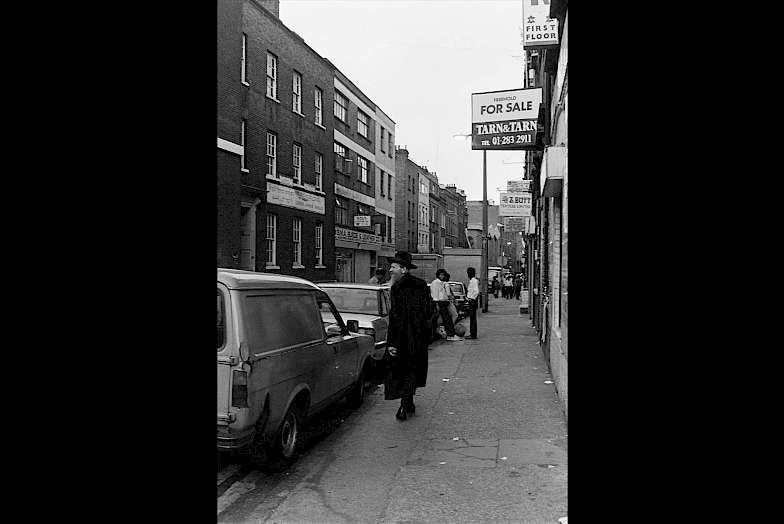

For centuries, Brick Lane has been a place of arrival and settlement for migrants from all parts of the globe, for whom this corner of East London became home. The East End’s proximity to London’s docks and to the City of London, its cheap housing and the ready availability of low paying manual jobs, made it place where new migrant arrivals landed, settled and raised generations of their families.

In the 1570s, Huguenots from France arrived in the East End as refugees fleeing religious persecution in Catholic France. Many of these refugees had been involved in the textile trade in France, as merchants and silk weavers. On arrival in East London, a number of Huguenots opened silk-weaving workshops, thereby establishing London’s silk industry. In 1914, there were still 46 silk weaving workshops in the Bethnal Green and Spitalfields areas of East London.

Migrants from Ireland began to arrive in the East End from the 1700s. Many found work on London’s docks, where they loaded and unloaded the products of imperial trade. The number of migrants arriving from Ireland dramatically increased by the late 1840s. They came to find work and escape starvation during the Irish potato famine. At around the same time, the East End also saw the arrival of ‘internal’ migrants from rural England in search of work.

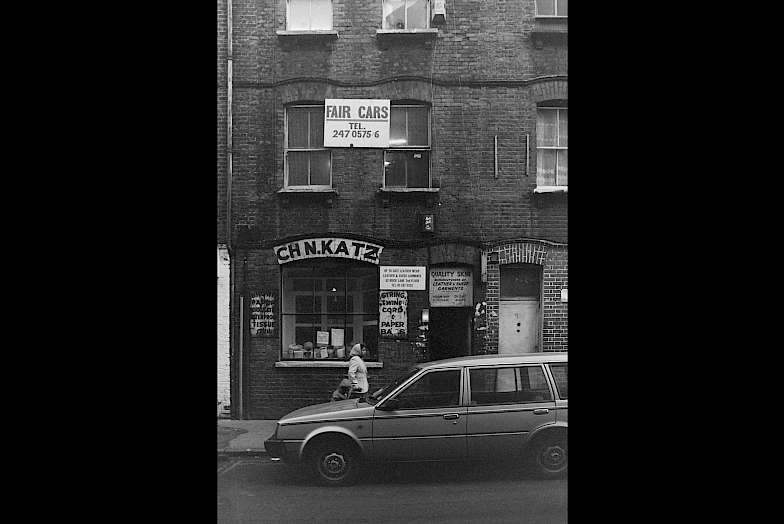

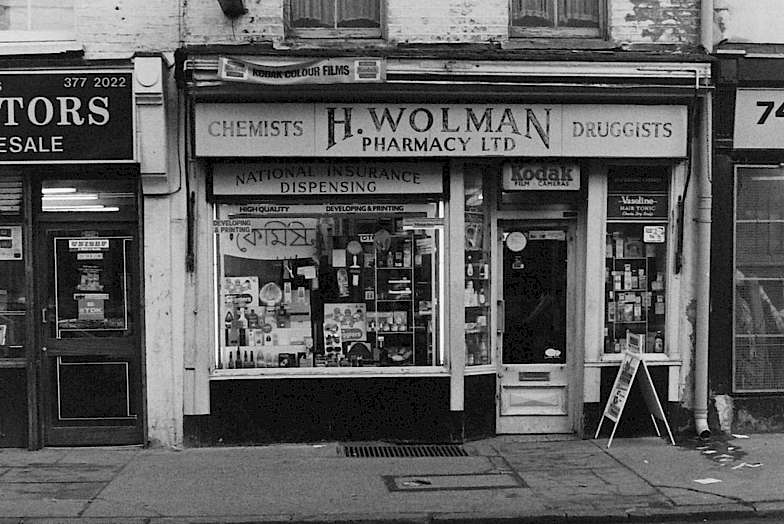

Small numbers of Sephardi, or Spanish, Jewish people migrated to the East End from the 1650s, fleeing persecution by the Spanish Inquisition. Many of these people arrived in London via Amsterdam. From the mid-1700s onwards, Ashkenazi Jewish refugees escaping from Germany and Central Europe began to arrive. These migrants were largely poor pedlars and traders, who found work selling second-hand clothes in the market stalls of London’s ‘rag trade’.

The largest number of Jewish settlers in the East End arrived from Eastern Europe in the period from 1881 onwards. Many arrived poor, with little knowledge of English. By 1899 a quarter of the population of Spitalfields was Jewish. In 1905, the Aliens Act, Britain’s first piece of legislation to restrict the entry of foreign-born migrants was passed in response to this increased Jewish presence.

In her book On Brick Lane, Lichtenstein describes Jewish Brick Lane in the period between the 1880s and the outbreak of the Second World War:

‘There were printers, hairdressers, drapers, greengrocers and tobacconists. Milliners, leather manufacturers, wine sellers and boot repairers among others. Most of the shop signs were written in Yiddish and English and the street was known as "Little Jerusalem".’ (Lichtenstein, 2008:3)

The start of the Second World War saw another wave of Jewish migration to the East End, this time of refugees escaping persecution in Nazi Germany. Among them were the owner of Brick Lane’s Epra Fabrics and his family.

There is a long history of migration of people from the Indian subcontinent to the East End, and to Brick Lane in particular. From as early as the seventeenth century, seafarers from the Sylhet region, in the north-west of what is today Bangladesh, began to arrive and settle in the East End. They came by way of East India Company and, later, imperial trading routes. From 1857, when the British Crown took control of India, these seamen arrived and settled as subjects of the British Empire. This small seafaring community in the East End also included seamen from other parts of the British Empire such as British Somaliland in East Africa.

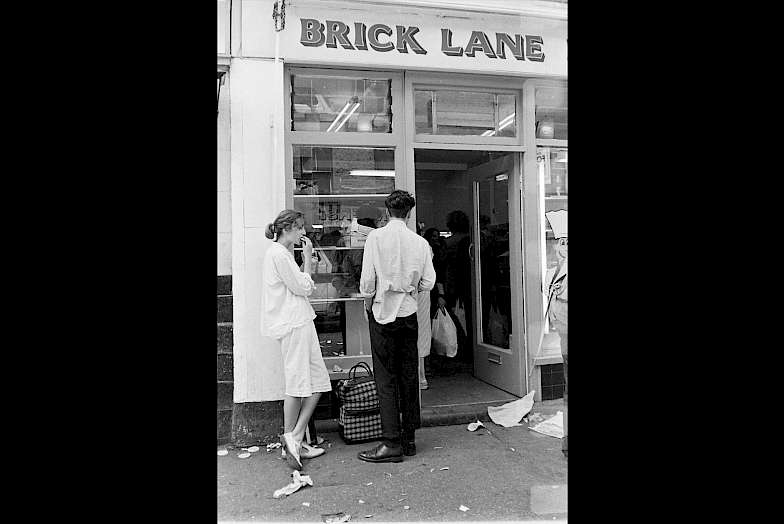

After the Second World War, the small, settled community of Sylheti ex-seafarers in the East End grew rapidly as increasing numbers of Commonwealth citizens from newly independent East Pakistan and, later, Bangladesh began to arrive and settle. Among these arrivals were the Bengali men who opened up, cooked in and served customers in Brick Lane’s now famous curry restaurants.

The most recent migrants to arrive in the East End include Somali refugees, who fled civil war in the 1990s, and, more recently, migrant workers from Eastern Europe.