As the Bangladeshi community in and around Brick Lane grew and became more established in businesses and local politics, the idea for a new commercial concept called Banglatown emerged.

The development of Banglatown was underpinned by regeneration money in the 1990s, with the involvement of Cityside Regeneration and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, to explicitly transform the area as a restaurant and cultural quarter.

The idea to rebrand Brick Lane along these lines originally came from a small group of local Bengali restaurateurs and community activists. Their community-oriented vision included plans for a ‘Banglatown’ shopping centre on Brick Lane selling ethnic food and crafts, more social housing and land for a community trust. The aim was to create a cultural quarter in the East End that would replicate, at least in part, the social and economic success of Chinatown in the West End and mark the presence of Bangladeshis. Their plans, however, stalled.

In the early 1990s, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in partnership with local businesses and third sector organisations, successfully bid for government regeneration grants to facilitate the development of Brick Lane into an ‘Emerging Cultural Quarter. The ‘City Challenge’ regeneration scheme, which ran from 1991 to 1996, was worth £7.5 million a year for five years. Its successor scheme, the Single Regeneration Budget (1994–2007), which operated through partnerships between the London Borough of Tower Hamlets and the City Fringe Partnership (1997–2002) and ‘Cityside’ (1997–2004), had a total programme spend of approximately £42 million in the area.

These schemes sought to redevelop Brick Lane, along with Whitechapel Art Gallery and the Rich Mix centre, as a cultural destination for young and affluent visitors from nearby offices and other parts of London; to strengthen the area’s links with the City; and to encourage diversification of the local economy. The aim was to draw on Brick Lane’s diversity and distinctiveness to create a ‘corporate creative culture’ in the area. Under the local authority, the Banglatown concept stood for the restaurant sector alone, rather than reflecting the full, rich, historical and cultural contribution of Bangladeshis in the area.

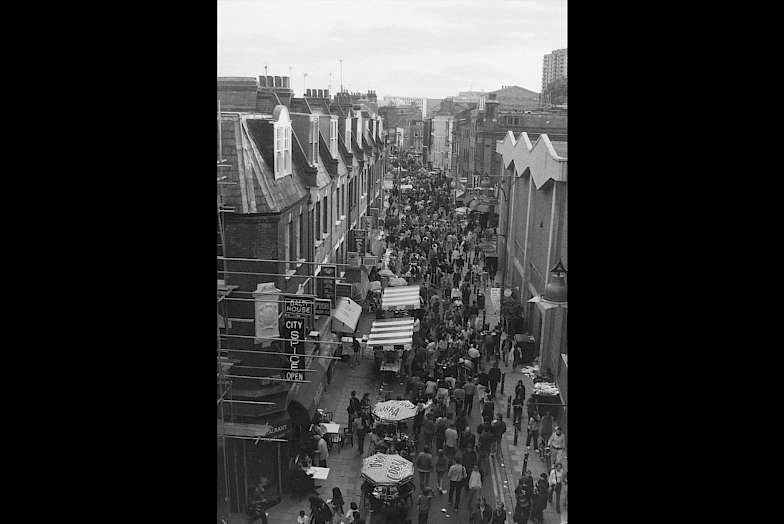

In 1997 the London Borough of Tower Hamlets officially renamed the short stretch of Bangladeshi restaurants that crowd the southern end of Brick Lane as ‘Banglatown’. The Banglatown development brought ‘Eastern’-style gateways to the street, painted streetlamps, measures for increased public safety, grants to upgrade the facades of existing shops and restaurants, and business advice for their owners. The Banglatown brand was used as a marketing tool to promote new annual street festivals on Brick Lane: the Boishakhi Mela, the Brick Lane Festival and the Curry Festival. In 1999, the borough’s planning office also permitted the conversion of shops in the central section of Brick Lane into restaurants, designating the area a ‘Restaurant Zone’.

The ‘Restaurant Zone’ designation prompted a boom in the number of Bengali-owned curry restaurants on Brick Lane. A Brick Lane restaurateur who converted his shop into a curry restaurant in the 1990s said:

‘the restaurant trade was coming slowly, picking up, so I thought, you know, 'I'm going to have a go at this and see how it works.'

A former local resident and community worker said of this period:

‘And then come, I guess, '90s, you know, the clothing business went down and the Bengalis became more creative and acquired some of the ground floor outlets and converted them to the Indian restaurants that we know of today’.

Other than a few restaurants like Café Naz and Bengal Cuisine, which offered more upmarket menus and service, and a few cafés like Café Grill, Graam Bangla and Sweet & Spicy, which served ‘home-style’ Sylheti food, the vast majority of curry houses on Brick Lane served similar Anglo-Bangla dishes, adapted for a British customer base, at a more or less identical cost.

The proximity of the street to the City of London meant that, during the day, office workers could easily walk to Brick Lane for a cheap and tasty lunchtime or after-work curry. One Bengali restaurant owner, who opened his Brick Lane establishment in the late 1990s, estimated that around 60% of his customers were City workers. He said:

‘when we opened, we used to have booking from many big offices from the City. Also, from the [London Stock] Exchange.’

Another restaurant owner said:

‘It was the trendy thing to come to Banglatown to have a curry and so on. All the City people used to come here. And while there, they used to spend money and so on.’

The redevelopment of The Old Truman Brewery and the opening of Vibe Bar in the mid-1990s saw the simultaneous birth of Brick Lane’s creative and vibrant night-time economy. A younger, predominantly white, middle-class, ‘creative’ crowd was now drawn to Brick Lane. These people frequented Brick Lane’s new late-night leisure spaces, where they drank and danced the night away before heading for a curry in the early hours. This provided an opportunity for some Bangladeshi-owned restaurants to open after midnight.

By 2003 there were 46 curry restaurants on Brick Lane, and at its peak the number of such establishments in and around the southern end of Brick Lane reached over 60. It became the biggest concentration of curry restaurants in Britain, known as ‘the curry capital of Europe’.