During the 1920s and 1930s, as increasing numbers of Sylheti lascars found themselves ashore and in search of work in the East End. Many forged new livelihoods as pedlars, kitchen porters, cooks and tailors in the Jewish-owned clothing trade.

Those who arrived in the post-1947 years followed patterns set by earlier Bengali settlers, finding work in East London’s textiles and garment workshops. Other new arrivals settled further north in Bradford, Oldham and Birmingham to work in textile mills or car and steel factories.

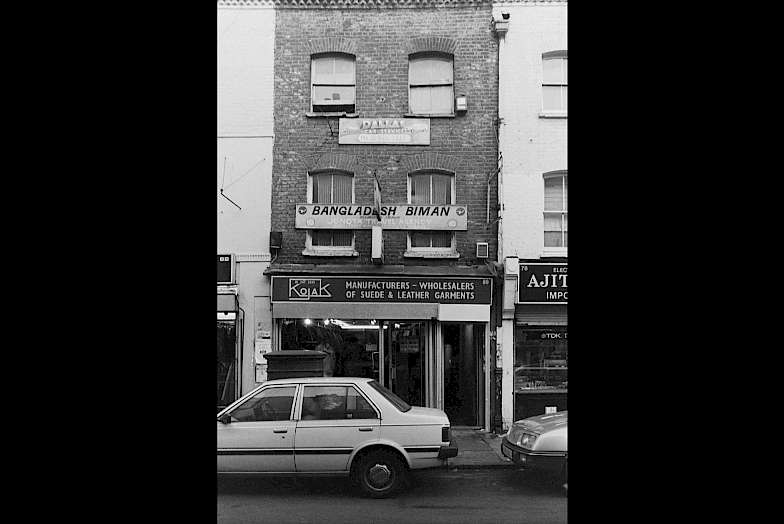

Bengali migrants formed an important part of the East End’s clothing and leather manufacturing workforce. Since the establishment of the silk-weaving industry by French Huguenot refugees in the seventeenth century, Spitalfields had come be known as the centre of London’s textile industry. From the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe found employment in East London’s ‘rag trade’. Soon, Jewish entrepreneurs dominated the garment, leather goods and tailoring sectors in the area, transforming former weavers’ looms into Jewish-owned ‘sweatshops’, where masses of cheap clothing was produced by cheap labour.

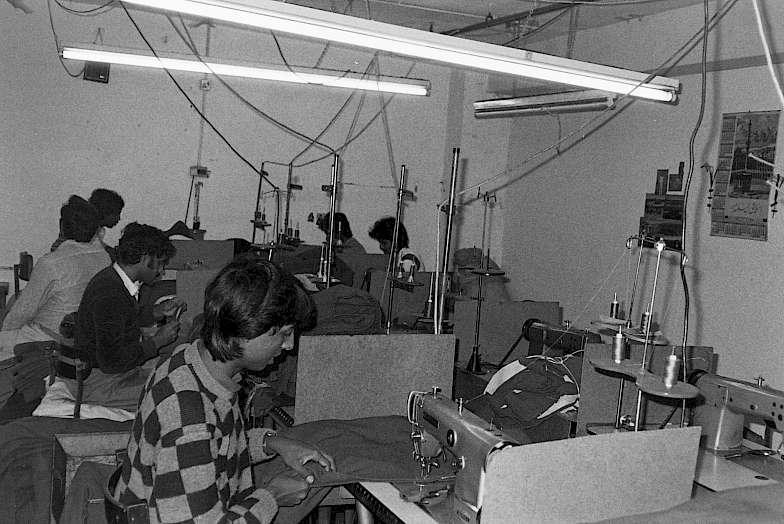

Some of these Jewish sweatshops were eventually taken over by enterprising migrants from newly independent West Pakistan. In the 1950s and 1960s, Bengali men made up much of the cheap labour force in these Jewish- and Pakistani-owned sweatshops, working long hours as machinists, pressers and tailors. A handful of Bengalis eventually opened their own East End leather and suede businesses.

One local business owner, who opened his store in 1956, said of Brick Lane at the time:

‘there was a lot of poverty around here. When I started, there was poverty. People lived very poorly. People had very poorly paid jobs. People in the tailoring trade and so on – they were very poorly paid jobs. There was no security in those days.’

A successful Brick Lane restaurateur, who started his working life in a Brick Lane clothing factory recalls:

‘we used to do a lot for Debenhams. And Selfridges clothing. Well, that’s the tradition: East End production, West End retail.’

A former local resident and community worker said of the clothing factories in and around Brick Lane in the 1970s:

‘the ground floors were showrooms, the basement and the first and second floors were the factories where people were machining, cutting and stuff.’

He continued:

‘I think they were owned by Jewish, by Turks, by Pakistanis, by Indians – and Bengalis worked in them. They were the cutters, they were the machinists.’

Another Brick Lane restaurant owner told us:

‘Rampart Street was where the main tailors were in the East End – that used to make the leather jackets. Because that's kind of what the Bengali community went in to doing really. I'd say that was their first major industry. Even before like restaurants, it was tailoring.’

In the 1970s, the number of Bengalis in search of work in the East End began to quickly grow. This was, on the one hand, due to increasing numbers of Bengali migrants, especially women and children, arriving in the East End in the years after Bangladeshi independence. It was also due to the increase of ‘internal’ migration into the area of earlier Bengali migrants who had, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, settled in Britain’s northern manufacturing cities. When deindustrialisation in the 1970s caused the cotton, textile and steel mills in these northern cities to close, leading to increasing unemployment, many of these Bangladeshis relocated to the East End in the hope of finding work. These ‘internal’ migrants found work in the clothing industry. Some also found employment as cooks and waiters in the growing Bengali-owned restaurant sector in and around Brick Lane.

In the 1980s, the East End’s clothing manufacturers were no longer able to compete with the cheaper clothing being manufactured in and imported from other parts of the world, including in Bangladesh. A former textile worker, who went on to open his own curry restaurant, said:

‘it was because the production of these garments is more cost effective, [done] more cheaply from Morocco, from Turkey, from Pakistan. Because a lot of leather companies, manufacturers, they started operating from Pakistan.’

This resulted in the out-migration of Jewish factory owners in the area and the closure of local textiles and leatherworks factories where many Bengalis were employed.

These are the conditions that led Bengalis in the East End to turn increasingly to catering as an alternative livelihood. In the 1970s and 1980s, Brick Lane’s Bengali-owned cafés were transformed into a growing number of outward-facing curry restaurants, which adapted their menus to attract a largely non-Bengali clientele.